Today it’s accepted that fiction (broadly defined; I’m including film and TV) can describe war in a realistic fashion. Stories aren’t required to be realistic, but they’re permitted to be. Until quite recently, that wasn’t the case. (I remember very vividly being called a pornographer of violence by Analog because I was trying to describe war as I’d seen it from the loader’s hatch of a tank in Cambodia.) That may be part of the reason why very few WW II veterans wrote Military SF.

Robert Heinlein and Gordon R Dickson wrote the most memorable military SF of the 1950s, but they had no combat experience. Mr. Heinlein served briefly as a naval officer in the ’30s before being invalided out with tuberculosis, while Gordy had asthma and spent WW II mowing lawns on army bases in California.

There were combat veterans who were prominent in the SF field at the time, but they were not prominent in Military SF. Herbert Gold, the founding editor of Galaxy, had been a grunt involved in the brutal fighting for Luzon, where nearly 300,000 Japanese soldiers were killed, but his magazine was the last place you’d look for Military SF. (Dorsai! was serialized in Astounding, later Analog; while the serial form of Starship Troopers appeared in F&SF.) Similarly Walter M. Miller had flown as air crew in B-25 bomber operations in Italy, including the mistaken attack on the Monte Cassino monastery.

Miller wrote and Gold published Command Performance, a devastating look at how Post Traumatic Stress Disorder feels from the inside, but the form of the story has nothing to do with war or the military. PTSD drove both men out of the SF field before the decade was over, but they were unwilling to confront it directly in print.

Miller wrote and Gold published Command Performance, a devastating look at how Post Traumatic Stress Disorder feels from the inside, but the form of the story has nothing to do with war or the military. PTSD drove both men out of the SF field before the decade was over, but they were unwilling to confront it directly in print.

I can only think of one exceptional Military SF story by a (probable) combat veteran before Joe Haldeman, Jerry Pournelle, and I started writing in the late ’60s. That story is Keith Bennett’s The Rocketeers Have Shaggy Ears, which I’m going to discuss in this essay. First, however, I need to provide some background.

2.

For reasons which will become clear, I have to use real names in this essay. I’m going to describe certain incidents as enlisted soldiers believed them to have happened.

Our beliefs may be completely mistaken; certainly they differ considerably from the language of the award citations which the Army accepts as the truth. For the purpose of this essay all that is important is that my fellow troopers at the time acted as though what I’m about to describe was true.

3.

The 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, the Blackhorse, was the spearpoint of the Cambodian Incursion of May-June, 1970 (the legal invasion, as distinguished from the bombing and black operations which had been going on for years). It was—we were—a crack unit, as fine a combat force as there was in Southeast Asia. The Regimental Commander, Colonel Donn Starry, was in the first vehicle across the border.

The North Vietnamese Army responded by running as fast as it could, but quite early in the operation an NVA soldier was spotted ducking into a bunker. Colonel Starry, with the Regimental Sergeant Major and the regiment’s chief interpreter, decided to talk the enemy soldier into surrendering.

Things seemed to be going well, but the NVA threw a grenade when the Colonel stood up. The blast injured all three friendlies involved in the negotiations as well as the Regimental Operations Officer, Fred Franks, who had just arrived by helicopter. (Despite losing his left leg, Franks went on to command the (coalition) VII Corps in the Second Gulf War.)

According to his award citation, Colonel Starry was wounded in the stomach. According to the medic who worked on him before the dust-off bird—the medical evacuation helicopter—arrived, his most serious wounds were well south of the stomach.

The Colonel was evacuated to Japan. We troopers laughed our collective head off when we heard that the Army had flown his wife there to meet him. To us it was an amazingly cruel joke—and the Army itself had perpetrated it.

You don’t find spit and polish in a real combat unit. You don’t find reverence either. Remember that point.

What happened to that brave NVA soldier? The platoon sergeant rolled his tank up to the bunker and put a round into the opening from as close as he could get the muzzle of his 90 mm main gun. It’s what he would have done first off if the Colonel hadn’t decided to look for a medal. In the Blackhorse we laughed at a lot of things that civilians don’t find funny, but we had no sense of humor toward people shooting at us.

4.

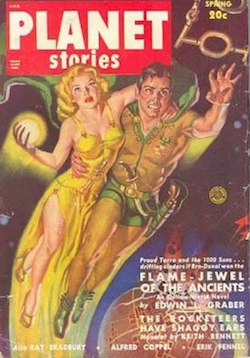

The Rocketeers Have Shaggy Ears was published in the Spring, 1950, issue of Planet Stories. It is the only SF story with the byline Keith Bennett, but three stories over the period 1951-1963 were credited to K. W. Bennett, who may be the same man.

The Rocketeers Have Shaggy Ears was published in the Spring, 1950, issue of Planet Stories. It is the only SF story with the byline Keith Bennett, but three stories over the period 1951-1963 were credited to K. W. Bennett, who may be the same man.

The name isn’t a pseudonym. Harry Harrison interviewed for a job with the editor of a trade journal named Keith Bennett. Harrison asked if the editor was the Bennett who had written Rocketeers. He was—and he was so tickled at the recognition that he hired Harrison.

From context (I won’t put my reasoning here, but I’ll provide it to anyone who asks me) Bennett had been a junior officer in an Army infantry division which fought on the jungle-covered islands of the Pacific. I suspect he commanded a battery of 75 mm pack howitzers.

The plot is simple, as simple as that of the Anabasis: a ship crashes in the unexplored jungles of Venus. The thirty survivors of the crew have to cut their way to their base five hundred miles away. Their equipment includes a light tank, but most of the unit will have to march. They set out.

The viewpoint character is Lieutenant Hague, the young officer commanding the squad with the light cannon. Hague has been rapped on the head during the crash, and his initial observations are fogged, withdrawn. Hague’s emotional distance—his flat affect—continues throughout the novelette, long after the effects of the possible concussion would have worn off.

This flat affect is absolutely symptomatic of someone who has been in combat for any length of time. Civilians—and to my certain knowledge, reviewers who are civilians—tend to assume that material is written without overt emotion because the writer is a monster who doesn’t have an emotional reaction to the (horrible) events he or she is describing. Through Hague’s head injury Bennett, though probably a first-time writer, brilliantly avoided that misunderstanding.

He avoided being misunderstood by civilians, that is. The veterans didn’t need a crutch, because they’d been there themselves.

The unit finds marvels on its way, plants and animals and an abandoned city of cyclopean stonework. Some of the animals become pets, but the troops’ main concern with the city is where to site their cannon for the best field of fire. There are natives also, shadows in the jungle darkness, and they’re hostile.

The troops are under constant stress: from the brutal march, from the jungle and its creatures, from the weather, from the natives. And from the unknown, from fear that doesn’t have a shape yet.

A few men break down; they’re dealt with according to circumstances and to the needs of the unit. Mostly, though, they just go on until they die. A lot of them die.

They help their buddies as long as they can and bury them when help is no longer possible; and sometimes there isn’t even a body bury. The survivors march on.

There are repeated acts of individual heroism which nobody talks about or even thinks about: it was necessary and somebody did it. Maybe it was your turn this time, maybe it was somebody else’s turn. It happened and you survived; and you march on.

I don’t know of any work of fiction which better captures the unrelenting grind of continuous combat operations. Amazing things happen, but Hague observes them precisely, unemotionally. Hague is numb, and his fellows are numb. Everyone subjected to such conditions becomes numb, or they break.

At last the survivors come within reach of safety—they’re in communication with the base and a rescue party is on the way. Here they break into song and Bennett makes a subtle point which he couldn’t address head-on because of the obscenity laws on the books in 1949.

The troops sing The Rocketeers Have Shaggy Ears, and the fact that the song provided the story’s title shows how important it was. The text describes it as ribald and says that the lyrics after the opening line wouldn’t look good in print. This is literally true, but people who don’t actually know the piece in any of its manifestations probably don’t understand how very true the statement was. Certainly the readers suggesting lyrics in the letter columns of later issues of Planet didn’t, and I’m quite certain that Judy-Lynn Del Rey didn’t expect correct answers when she proposed a lyrics contest when Del Rey Books reprinted the story in the ’70s.

The version Manly Wade Wellman sang to me (as The Mountaineers; there are also Engineers, Pioneers, and Cannoneers, which last gave the title to a memoir by a field artilleryman) continues:

And go without their britches.

They pop their cocks with jagged rocks—

They’re hardy sons of bitches.

Further stanzas are of a similar order, but the first is enough to make the point that even today The Rocketeers wouldn’t be a song for polite society. The troops, men who have proved themselves heroic and enduring beyond civilian imagination, are giving the bird to society and to their own brass who are listening back at base. This is humor which deliberately distances the veterans from all those who haven’t paid what they paid.

A real combat outfit reverences nothing. I don’t think anyone can achieve a bone-deep understanding of that without having himself been in such a unit. Keith Bennett understood perfectly, and he made that understanding the point of his story.

5.

Blackhorse firebases—the squadron headquarters in the field, each with a battery of self-propelled howitzers—were often named for senior personnel who had been wounded. At Fort Defiance (a different naming convention: 2nd Squadron had set up in the middle of the Parrot’s Beak and dared the NVA to do something about it) Sergeant Major Burkett was wounded badly enough to be medevacked. Before the dust-off bird arrived, Burkett realized that his shirt was bloody and ran back to his trailer to get a fresh one. While he was inside a rocket hit the trailer, blowing his arm off.

When 2nd Squadron moved, the new position officially became Firebase Burkett. In the field, however, everybody called it Burkett’s Arm.

There was never a Firebase Starry. We troopers believed that the brass was afraid that some journalist would hear us refer to it as Donn’s Dick.

Keith Bennett and his Rocketeers would have understood.

You can read The Rocketeers Have Shaggy Ears here.

Bestselling author David Drake can be found online at david-drake.com.